The roles of fathers have evolved over the generations. Dads who survived the Great Depression were not the same as dads who had served in World War II. Dads who were part of the Hippie Movement and Free Love in the 60’s were not the same as the dads who came of age in the “Greed Is Good” era of the Eighties, and so on.

The days of fathers having stoic personalities and emotionally distant providers to their children is over.

When my wife and I decided that we would be foster parents, one of the first things we learned in our training to be licensed as foster parents in the state of Arizona was that my role as a male parent was just as important as a “mom” in the development of a child’s emotional growth as well as mental well-being.

In a piece by the Wall Street Journal, a new survey of more than 1,600 teenagers by the Harvard Education School’s Making Caring Common project is finding that almost twice as many 14-to-18-year-old boys and girls feel comfortable opening up to their mothers (72%) as to their fathers (39%) about anxiety, depression or other mental-health challenges. The wide disparity in the statistics suggests that dads need to become, or evolve into a much more nurturing, emotionally available parent and by being much more involved at home, dads can offer the kind of emotional support that many children today so urgently need.

A literature review just published in January in the journal Infant and Child Development looked at nearly four dozen studies on father-child relationships. What the review found was the role that dads play in building a child’s skills in regulating emotions and fathers who reacted with greater sensitivity and warmth to a child who expressed their emotions, were significantly more likely to have children with better emotional health from infancy to adolescence. But children who didn’t have those kinds of interactions with male parents had poor emotional regulation skills. The lack of being able to regulate emotions in children are linked with anxiety, depression and behavioral problems in adolescence and adulthood.

I was scared to become a dad. I never thought I had the natural, intuitive ability to raise a child, especially a boy. I shied away from children as I grew into adulthood, dated women who didn’t want children, and never saw myself as a nurturing, loving person who had the emotional IQ and ability to handle be a parent.

My 1-year-old son and I building a playset in 2018 in their backyard in Phoenix, Arizona. My son insisted on wearing hearing protection. (Photo courtesy of Mac Watson).

So when my wife came to me in 2016 and said she felt a calling that we should be take the necessary and crucial steps to be a foster parent, I balked. I was in my 40’s at this point and thought I (we) were way past the stage to even consider having children, let alone being so-called “experts” on how to be foster parents.

But one evening, my wife and I were at a fundraiser. A woman who was a CEO of an agency that taught guided would-be foster parents said something that struck me. “When you think you can’t, you can.” She was talking about supporting her organization by giving money, volunteering, working at the center. I heard it differently. From that moment on, every time a thought entered my mind that I couldn’t or wouldn’t be a parent, her quote would remind me that we had the means, the courage, the ability to open our home to children who needed our help the most. So we began the process.

Boys are especially affected by whether dads who are part of the emotional equation. Because many men didn’t grow up with an emotionally warm male role model, they may lack confidence in their own abilities to be sensitive caregivers. That was me. In foster care training, my wife and I learned that men need to take a more prominent role in allowing children to express themselves and by being distant or shut down will only continue the pattern that our culture has instilled in men for generations. Men are not emotional, boys don’t cry, men “fix” things, boys have to toughen up, be strong,” and cannot be weak in showing their emotions.

My son sometimes would fall asleep as we ate dinner. As hard as he tried, sometimes he just couldn’t stay awake. (Photo courtesy of Mac Watson).

I was determined not to be like my father. But, I found out, that was easier said than done.

“When women take on the role of being the sole emotional caregivers, the only one who can comfort a child, the one who talks about emotions, it further entrenches the idea that the expression of vulnerable feelings belongs in the domain of women,” says Lisa Damour, author of “The Emotional Lives of Teenagers: Raising Connected, Capable, and Compassionate Adolescents.” She adds, “It’s not enough to encourage our sons to share their inner worlds. The men they look up to and respect need to show them how it’s done.”

Matt Schneider, co-founder of a national support group for fathers called City Dads Group, says that dads need to challenge and push back against the stereotype that men are less capable of being sensitive than their female counterparts. That’s the myth that has fueled so many men push down their emotions in order to not raise “sissies” for sons.

Fathers don’t need to accept the proposition that they are inherently less nurturing, says Mr. Schneider. Learning how to be a warm, emotionally attentive parent, he says, simply “involves on-the-job training and staying actively engaged until you start getting good at it.”

When my wife got the call in 2017 that a brother in sister had entered the foster care system and needed placement, I felt my stomach sink into my bowels and my anxiety soar into the stratosphere.

This would be our first placement as foster parents after going through childcare training for six months. Six months of me saying to myself that there would be no way we would be approved by the state of Arizona to take care of children who were removed from their home because of abuse or neglect.

Matt Schneider of City Dads Group, says fathers don’t need to accept that they are inherently less nurturing. Learning how to be a warm, emotionally attentive parent, he says, simply “involves on-the-job training and staying actively engaged until you start getting good at it.”

My wife and I both didn’t have ideal childhoods (that’s putting it mildly and succinctly) and I discovered through the training process that for many reasons, I had been in denial about numerous circumstances in my childhood.

Stories that I would tell at parties or in social situations about being raised as a Generation X baby by parents who grew up with their parents who had survived the Great Depression, would sometimes be greeted by awkward smiles and in rare cases, an apology after my story was over. Things that I thought made hysterical tales, things that I thought were normal, or at least acceptable, wasn’t the norm in many families. But I didn’t know that.

So when that phone call came, that two children who were 7 and 11-months old at the time, would be placed with us as the state of Arizona did approve and certify us to be licensed foster parents, I panicked. How could I, as flawed and in denial as I was about my own rearing, be someone who could help these two kids who needed services, support, guidance, and most of all, unconditional love? All the things I learned about nurturing, loving unconditional, effects of childhood trauma and neglect, would become real in a matter of hours.

As my wife and I nervously drove down to a non-descript office building in downtown Phoenix, all I could do was look at my wife and hope to God she remembered more than I could recall about our training, because I was blanking. All I could remember from training was what we could be in for as we were introduced to the kids who would be our responsibility for the near future.

“Think about being a child,” the one social worker explained at our dining room table in the middle of winter at our home in Phoenix. “Someone knocks on your door. It’s a stranger whom you’ve never met. They could be of a different race, a different ethnicity than your family — not familiar at all. You are told you must leave the only family you’ve ever know, bonded with (whether there was trauma bonding or not) bring some things (if the child is lucky) like a stuffed animal or a blanket and, in most cases, just the clothes on your back. That’s what the child will experience when being removed from their home by the state for their protection.” I remember the social worker then describing how children taken from their homes by the State have separation issue, abandonment issues, anxiety, and in some cases, becoming angry and violent.

That’s when foster parent training became real for me. It triggered all these feelings of when I was a child and gave me flashbacks. Not that I was ever in foster care, not that I was ever taken from my parents, but the feeling of abandonment and sadness was a profound reaction I had as an adult.

So when we parked our car in the parking lot and was buzzed into the building, all I kept thinking was what kind of emotional reaction would those kids be having and could I handle it? Like a foster parent once told me during our training, “It can kick up a lot of your own shit when you pick up those kids.” Gosh, was he not kidding.

My wife and I had a plan that we devised and discussed on the drive downtown. She would take the 11-month old boy since she loved babies and I was deathly afraid of them since accidently dropping my six-month old cousin when I was eight and being punished and shamed for it.

I was to interact with the seven-year-old girl, since I was better (not great) with children who could speak and I could hold a conversation with.

This is my daughter. She’s a fighter. Always has been, always will. She is fierce. Watch out, world. (Photo courtesy of Mac Watson.)

When the paperwork was finally filled out and we were led down a hall, past a series of offices, we were led into a common room that had a conference table, chairs, and tables that had stacks of boxes on them. Diapers, formula, duffel bags, clothes, and blankets were all in the boxes, ready to fill duffel bags for the kids who were now the State’s wards.

In the room a couple of social workers were busy filling duffel bags, holding and talking to children, and filling out forms. By now, it was 8PM at night and some babies were sleeping.

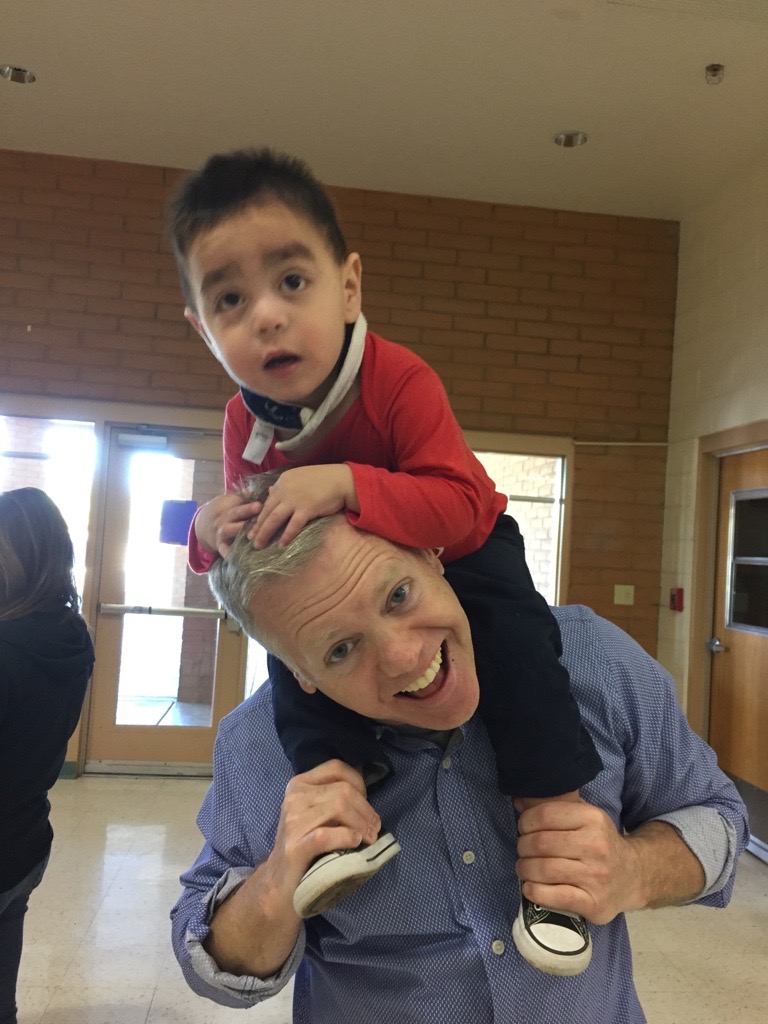

The social worker took my wife and I to the far end of the room. A little girl was staring at the floor, crying as tears streamed down her cheeks. Standing next her was another social worker who was holding a baby with big, bright brown eyes, who was in a new onesie. As we approached the children, the social worker who had led us to them began to introduce us. I walked toward the little girl but suddenly, the boy, the 11-month old, lunged from the woman’s arms who was holding him and with a big smile, looked at me and reached out his arms. He wanted to come to me. Not my wife, not another social worker, not another woman, but me.

I awkwardly caught him and held him out at arm’s length as he took me in and with his big smile, opening and closing his tiny fists. Looking back, I realized, I didn’t choose him. He chose me.

My wife bent down to try to console the little girl who was crying on the floor. The social worker told us her name and my wife whispered and said hello.

I asked the social worker what was the name of the little boy that I was now cradling in my arms. She said the name. I looked at him as the little girl on floor corrected the social worker. She had been mispronouncing the little boy’s name and now his sister was declaring how to say his name correctly. We quickly learned that this little girl was a fighter. Defiant. Fierce. Sadly, she had been parentified and she spoke for her little brother a lot. The little boy, whose name had been mispronounced in foster care until that moment was a little, round bundle of smiles and dark, expressive eyebrows, whose name people still mispronounce to this day. And he chose me.

That’s how we met the kids, who six months later, would officially become our son and daughter.

I am not a perfect dad. I struggle daily with how I can raise my son (and daughter) to be the best person they can be. It’s not easy, it’s hard, it’s infuriating, soul-crushing, it’s the most joy I’ve ever experienced.

My son still has dark, expressive eyebrows. My daughter is still fierce.

I am proud to be their dad, but even prouder that I am a loving, nurturing man who is their father and can laugh and cry and express myself and let them express all the hurts, fears, sadness, joys, exuberance, and happiness they have.

When you think you can’t, you can.

If you’re a dad, I hope you have a wonderful Fathers Day.